Three demos of animated svg gradients from designmodo.

Author: Lois Last

Framer Generator

Apple and Responsive Design

Apple has always had a funny relationship with responsive design. They’ve only sparingly used media queries to make minor visual tweaks on important pages, like their current homepage.

With iOS 6, and the subsequent release of the taller iPhone 5, Apple introduced something called Auto Layout—a relationship-based layout engine. Unlike the iPad, which required a separate build, apps for the taller iPhone were the same build with layout adjustments applied. Auto Layout was Apple’s first true foray into responsive design within native applications since, much like the web, different layout rules were applied to the same base code.

Last week, Apple introduced iOS 8, and with it, something they’re calling Adaptive UI. The main feature of Adaptive UI is the ability to specify layout rules based on Size Classes, which are really just breakpoints set by Apple.

Developers can now use a single View Controller (or page, in our world) with various layout rules applied across Size Classes (or breakpoints) to accommodate devices of all sizes. While there are only two Size Classes right now, compact and regular, Apple has left a lot of room to add more, or to even let developers set breakpoints themselves in the future.

It may be adaptive in name, and hard-coded breakpoints may seem like adaptive thinking, but the groundwork has been laid for responsive design within native iOS applications. It’s been interesting to watch Apple’s path from static, to adaptive, to responsive, and it’ll be even more interesting to watch third-party developers take advantage of the workflow benefits of responsive design that we’ve become accustomed to.

Everything You Need to Know About the CSS will-change Property

If you’ve ever noticed “that flicker” in WebKit-based browsers while performing certain CSS operations, especially CSS transforms and animations, then you’ve most likely come across the term “hardware acceleration” before.

The will-change property allows you to inform the browser ahead of time of what kinds of changes you are likely to make to an element, so that it can set up the appropriate optimizations before they’re needed, therefore avoiding a non-trivial start-up cost which can have a negative effect on the responsiveness of a page. The elements can be changed and rendered faster, and the page will be able to update snappily, resulting in a smoother experience.

Can the digital IKEA effect increase user engagement and brand loyalty?

According to behavioral scientists Michael I. Norton, Daniel Mochon and Dan Ariely, people who participate in the creation of something tend to evaluate what they have created more positively than they would have done if they had not participated in it. This is referred to as the IKEA effect.

Grid Style Sheets for Constraint-based Layouts

iOS-like Auto Layout applied to browser displays. Based on the same constraint algorithm.

CSS manages features like color and font selection quite well. But there’s an important fault at the core of CSS that rears its head when designing the actual layout of pages. Despite its declarative syntax it merely describes how a page will fit together, almost in an imperative way. An element will have so many pixels of padding, be a certain width, be floated right – but this doesn’t say anything about where it fits in relation to its neighbours and the page as a whole. It certainly doesn’t account for where it should be displayed on different sized screens, as this requires multiple definitions for a selector with media queries controlling the breakpoints.

Fortunately, there’s a better way. The solution is nothing short of the drastic solution of bypassing the entire browser layout engine, and replacing it with one that doesn’t suck. This way, we get to define what we want the layout to be, not how the layout should be constructed…

The solution is a JS library Grid Style Sheets, and it’s available right now for use in today’s browsers. It’s an implementation of the Cassowary constraint solver algorithm – the very same one used by Apple in its recent Auto Layout tooling – and it feels like something from the future. Note that this has nothing to do with traditional Layout Grids as used by designers, and available in CSS form – The Grid is the startup who has created GSS.

Import web pages into Sketch

Sometimes you need to tweak or slightly redesign an existing web page without original assets. Some common ways to do this would be to recreate a page from scratch, tweak it in a web inspector, or in the worst case make a screenshot and mess with bitmap (if you enjoy pain). Another hacky way to do that is to actually convert the web page to a vector graphic. Here is how I do it:

1. Convert page to SVG

Option one: Use http://derailer.org/paparazzi/ like so https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cgHQyXm4_Y to import a page into sketch. If it doesn’t work well try option two.Option two: Go to http://www.hiqpdf.com/demo/ConvertHtmlToSvg.aspx and insert the desired URL of a web page and the screen size.

Note: Sometimes you want to access a page behind a login, or an offline document. You can use this chrome extension http://cl.ly/VRdx to save a webpage as a single document and feed its internal code to hiqpdf converter.

Using the :target pseudo-selector for alternative layouts

I really like the :target pseudo-selector. It enables you to style the target of a so called skip-link. For instance when you link to a section in an article: you could highlight the header of that section. Or you can use it for toggling simple drop-down menus — the ones you see a lot on small screens. But you can also use it to create a completely different layout.

I used this technique on my Daily Rectangle site. As you can see (if your browser supports the vh unit) all the images are as high as the viewport. That’s nice, it enables me to enjoy one single image. But sometimes I want to see all the images on a grid. I could have created a PHP script that responded to a querystring. Or a small JavaScript. But instead I used the :target pseudo-selector. It’s very simple. First I did this…

Turn Marvel Prototypes Into iOS And Android Apps In Less Than 10 Minutes Using Appcelerator

For Marvel Pro users only. Also run locally.

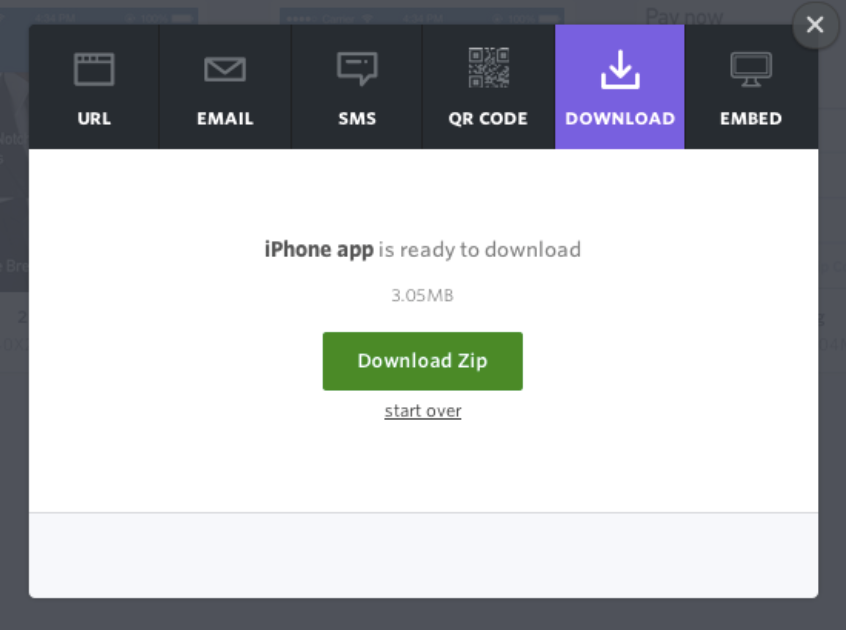

About two months ago we launched a feature for Pro users that allowed them to download their prototype as a zip file. The zip file contains the HTML, CSS and JS source files that Marvel uses to build your prototype.

This allows you to host, alter, mix up and play with your prototype on your local machine or server. It’s also really useful if you happen to be presenting and you’re not sure if you’ll land yourself in a situation that has a sketchy internet connection.

There is one other advantage to our downloadable prototype in that it’s fully compatible with HTML based app building platforms like Titanium, Phonegap, Cordova. The following tutorial video gives you an overview on how to run the integration with Titanium.

The new srcset and sizes explained

Uses picture/srcset/sizes polyfill picturefill 2.

There are now two responsive images solutions which can be combined or used on their own. This article focuses on the simpler one, which will do for almost all responsive content images, which aren’t art directed and should just stretch and squish with max-width: 100%;.

Until now we used media queries to determine which size the viewport is and which pixel density the screen has and load a specific source according to that. With srcset we don’t need that anymore.

We don’t tell the browser which source it should display at which screen size and pixel density, because that is inflexible and lead to dozens of lines of code and definitions just for one single image. Even worse, it’s not really future proof and we only support pixel densities that we defined. What if a 4x screens comes along tomorrow? Did you write media queries to support that? I haven’t. But with srcset we are covered.

What we do with srcset and sizes is, we tell the browser which sources, aka files, it has at its disposal and which width they have. Then we also tell the browser how wide the image should be displayed at any given viewport width. The browser now knows everything it needs to know to decide which image is appropriate to use. I like to imagine the img tag as a container. We as developers only define how big the container should be at any given point and the browser decides which source to load to get the best output for the user.

<article>

<img srcset="large.jpg 1400w, medium.jpg 700w, small.jpg 400w"

sizes="(min-width: 700px) 700px, 100vw"

alt="A woman reading">

</article>>

* {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

}

article {

margin: 0 auto;

max-width: 700px;

}

img {

max-width: 100%;

}